Paper Summary 4

Introduction

This summary specifically focuses on the low-resource scenarios for text summarization where a very limited number of data is annotated (and we may or may not have access to some other unannotated data).

- Paper:

Abstract Text Summarization: A Low Resource Challenge [paper]

- Background and motivation:

Datasets for multilingual text summarization are very hard to construct; thus, in this work, a data augmentation technique is proposed to conduct abstract text summarization in German.

-

Solution:

The idea of augmenting the low-resource annotated data is originated from the “back-translation” idea in NMT. In detail, when doing NMT, if we have a group of labeled data from the source language (e.g., En) to the target language (e.g., Fr): $Annotated=\{(En\longrightarrow Fr)_i\}_{i=1}^N$ and a group of unannotated data in the target language: $Unannotated=\{Fr_j\}_{j=1}^M$. And usually, the model will be quite insufficiently trained if we only apply the $Annotated$ dataset. Thus, we need to convert the unannotated dataset (in target language) into annotated version. A good method is to apply “back-translation”, where we first train a model from target (Fr) to source (En): $Fr\stackrel{bt}{\longrightarrow}En$ using the $Annotated$ dataset. And then we feed the $Unannotated$ dataset into our trained “$bt$” model to generate some synthetic data $En_{syn}$ to finally get our augmented dataset:

\[Augmented=\{(En\longrightarrow Fr)_k\}_{k=1}^{N+M}=\{(En\longrightarrow Fr)_i\}_{i=1}^N+\{(En_{syn}\longrightarrow Fr)_j\}_{j=1}^M\]Then the $Augmented$ dataset is used to train an NMT model from English to French.

Like NMT, in abstract summarization, with a small annotated dataset from text to summary and a large group of unannotated sentences (viewed as summaries), this paper proposes to first map the unannotated summaries to synthetic texts, and later use the augmented dataset (origin+synthetic) to train an abstract summarization model.

Highlights I think the highlight is the proposal of using back-translation to generate synthetic data for a low-resource setting in abstractive summarization. However, using back-translation has as well been under doubt and criticized (see [here]).

- Architecture:

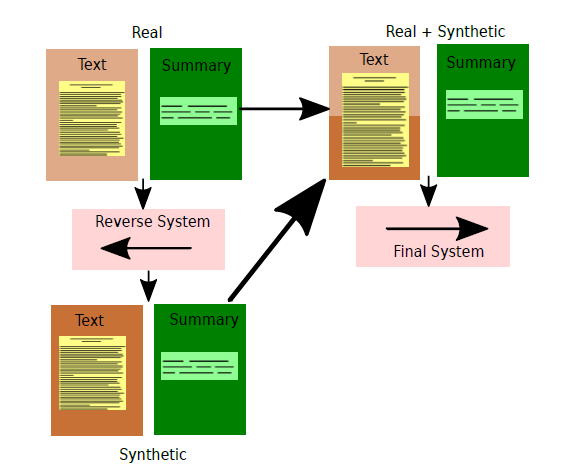

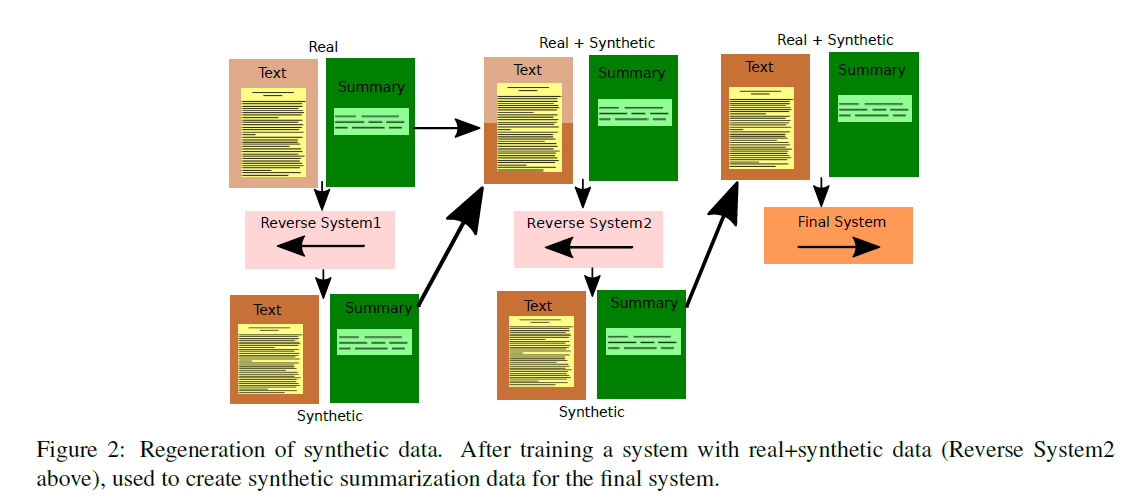

The back-translation architecture:

The “double” back-translation architecture (performs worse than above):

- Paper:

Long Document Summarization in a Low Resource Setting using Pretrained Language Models [paper]

- Background and motivation:

Abstractive summarization task with long documents in a low-resource scenario is under-explored. This work uses BART ( which is a powerful abstractive summarization model pre-trained on relatively short documents) and aggregates it with long document abstractive summarization.

-

Solution:

This paper proposes to compress the long documents using a transformer-based classifier (“Extractor”) where sentences labeled as salient will be the compressed version of original long documents. To prepare the training data for the classifier, GPT-2 model is used to ground the summaries $T$ (target) to the long documents $S$ (source), and a score $\frac{1}{n}\sum_{j=0}^nf(s_i,\,t_j)$ measuring how much one summary is grounded in each sentence of its source document. After scoring, an aggregated sampling method is proposed: some sentences with top-3n highest (salient) and top-3n lowest (non-salient) scores (n is related to the number of sentences in the summary $T$ and is a tuned hyperparameter) are selected as the positive and negative samples of the original long documents; then, these sentences will serve as our training data for the “Extractor”.

After using the “Extractor” to compress the original long documents, the compressed documents are fed to BART and then fine-tined. (Note that results for combinations of different sampling methods and $f$ are in the appendix, generally speaking, aggregated sampling + GPT-2 scoring is the best option)

Highlights One very surprising idea in this paper is that it does not use extra data, which really is my ideal “low-resource” setting. The following strategy is very straightforward: a. train a long document compressor using pre-trained models to prepare labeled data; b. then leverage BART to summarize the compressed documents. The whole process can be viewed as “purification”.

- Architecture:

- Paper:

ExtraPhrase: Efficient Data Augmentation for Abstractive Summarization [paper]

- Background and motivation:

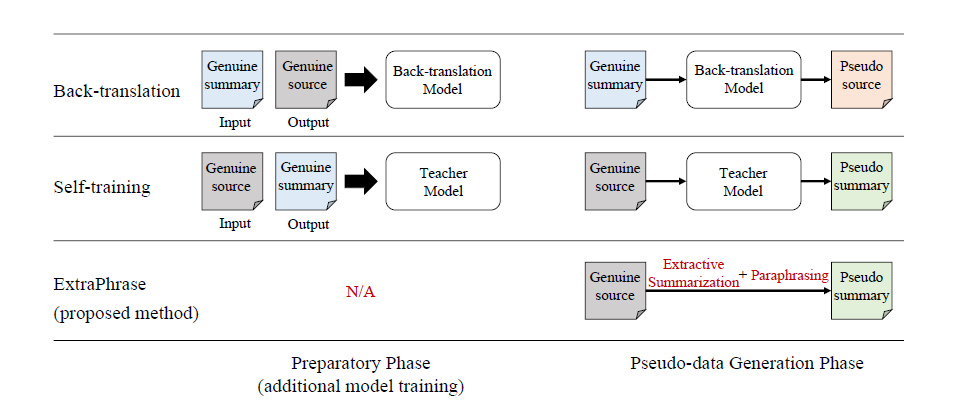

Previous abstractive summarization task in the low-resource setting usually needs a neural network to obtain synthetic data, this work proposes a new method that does not need pre-preparation.

-

Solution:

Unlike back-translation models (such as [this]) which need to first train a summary-to-text model in order to generate synthetic data, this work proposes to directly prune the parsing tree of a summary to generate its extracted version and uses round trip translation to generate paraphrases for the extracted summary. For round trip translation, this paper leveraged SOTA pre-trained NMT models, and the extracted summary (e.g., En) will be first translated into another language (e.g., De) and then translated back (e.g., De $\rightarrow$ En) to get the paraphrased version of the summary (the final pseudo summary). Later the generated summary and original data are used for training an abstractive summarization model.

Interesting experiments have been done to show the effect of the model. One is the normal setting, where genuine datasets of size 380M/287K are used to generate pseudo data. And the model achieved a very small gain on the ROUGE-1, 2, L compared with methods like back-translation, self-training, and oversampling by simply double the size of the dataset; The other is the low-resource setting, where the genuine dataset is only of size 1K and the rest data (3.8M) is used to generate pseudo data. Again, the ExtraPhrase has beaten all the comparing methods and achieved a great margin (e.g., 23.58 v.s. 12.19)

Highlights The value of this work to me personally is that it has revealed the drawbacks of back-translation as a data augmentation technique in abstractive summarization to me. The reason why back-translation is successful in NMT is that the meaning and amount of information stored in the source and target are approximately the same, however, for abstract summarization, it might be irrational to synthesize documents with richer, redundant information from a concrete, relatively smaller summary, since the back-translation has no guidance on how to recover information unseen in the documents. And as well, this work also shows us a good example of using light-/non- neural network methods to achieve comparable (under normal setting) even remarkable (under low-resource setting) results.

- Architecture:

- Paper:

Mitigating Data Scarceness through Data Synthesis, Augmentation and Curriculum for Abstractive Summarization [paper]

- Background and motivation:

This work proposes three data augmentation techniques for low-resource abstractive summarization tasks without using any additional data.

-

Solution:

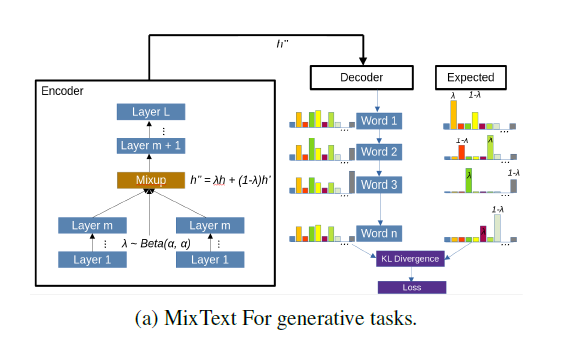

To achieve the augmentation without using any extra data, this paper proposes three possible solutions: a. synthesis via paraphrasing with GPT-2; b. augmentation with sample mixing; c. curriculum learning. For paraphrasing, the original summaries are paraphrased using the GPT-2 model. And for sample mixing, the original idea is to feed two sentences $x, \,x^{‘}$ into the same architecture and mix their representations with a proportion of $\lambda:1-\lambda$ at some layer and then the mixed representation will produce a probability distribution which indicates the “mixed” distribution of words in $x, \, x^{‘}$, which can be illustrated as:

where the KL divergence between the predicted distribution $\hat{y}$ and the “mixed” real distribution will serve as the loss function. In the paper, the authors propose MixGen, which has a decoder where for training, the ground truth distribution at each time-step $t\in[1,\,min(|x|,\,|x^{‘}|\,)]$ will be:

And for time-steps that exceed the value of the minimum length of $x,\,x^{‘}$, the word distribution will be that of the remaining of the longer sentence. When decoding auto-regressively in training, instead of using $argmax()$ to decide which token to predict (in this case it will always be the tokens with a higher weight of $\lambda,\,1-\lambda$), the ground truth token at time-step $t\in[1,\,min(|x|,\,|x^{‘}|\,)]$ is chosen based on a probability $P_t\sim U(0,\,1)$. The illustration for MixGen is:

For curriculum learning, data are fed to the model with difficulty from low to high, where the difficulty is measured by a pre-defined criterion (in this paper, there are two criteria, namely specificity (measured by a classifier) and ROUGE)

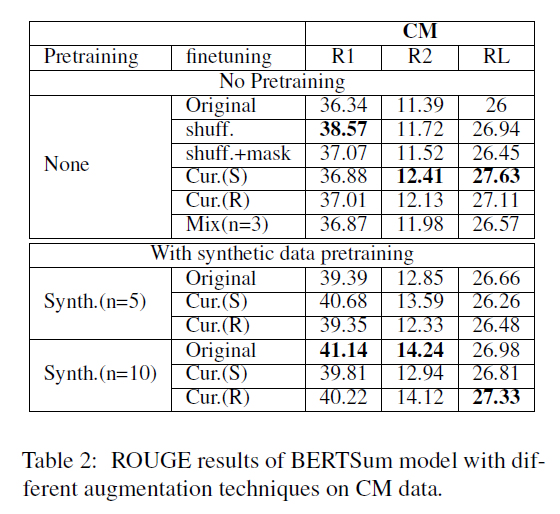

Highlights Unfortunately, though the authors have proposed some useful techniques and discussed them under a non-extra data setting, the experiments are quite disappointing:

As shown above, the “shuff.” according to the authors is a synthetic baseline constructed by generating 10 samples for each of the original training samples by randomly shuffling the texts, and “+mask” means randomly mask 50% of the texts 50% of the time. As you can see, the training data of “shuff.” and “shuff.+mask” though redundant (whose power is reported [here]), is much bigger than the original data, which leads to unfair comparison. Also, the pre-training synthetic data experiment did not include the Mix(n=3) method.

-

Architecture:

No specific overall architecture

-

Paper:

Few-Shot Learning of an Interleaved Text Summarization Model by Pretraining with Synthetic Data [paper]

- Background and motivation:

Interleaved texts are very common in online chatting where posts belonging to different threads occur in a sequence. Existing methods first disentangle the interleave texts by threads and then perform abstractive summarization, which may propagate errors if the disentanglement is wrong in the first place. And this work proposes to train an end-to-end summarization system with synthetic data interleaved from a regular document-summary corpus.

-

Solution:

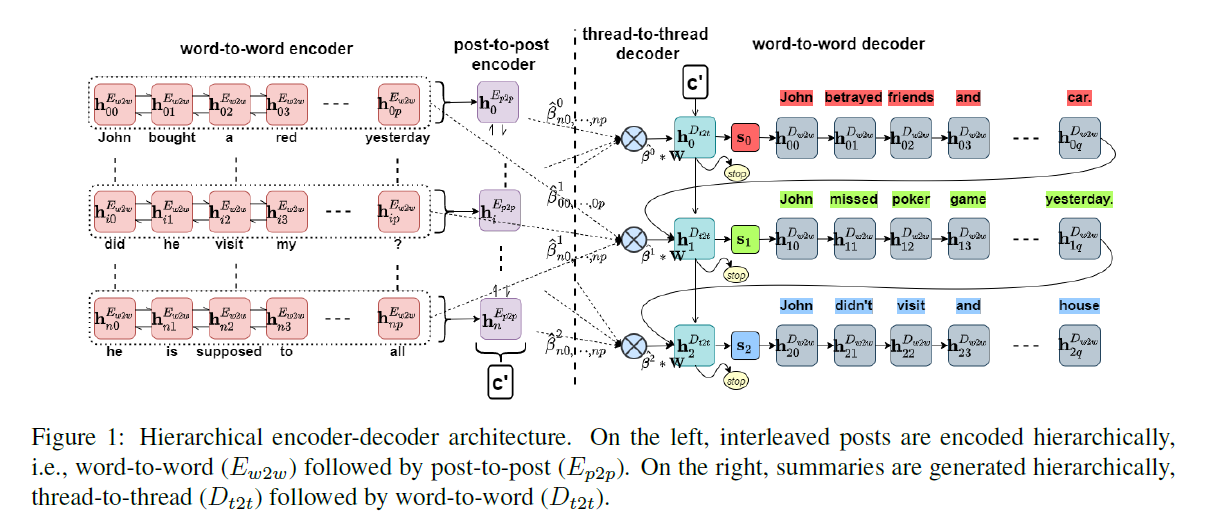

To deal with the disentanglement implicitly in an end-to-end system, this paper proposes to use hierarchical attention mechanisms to attend to word-level, post-level (or in other words, sentence-level), and thread-level features. The overall architecture is shown below.

When encoding, for the $i$-th post $P_i$, a word-level BiLSTM encoder $E_{w2w}$ first encodes the word embeddings of $P_i$ to get a sequence of hidden representations $(\textbf{h}_{i,\,0}^{E_{w2w}},\,…,\,\textbf{h}_{i,\,p}^{E_{w2w}})$, and the average: $\frac{1}{p}\sum_{j=0}^p\textbf{h}_{i,\,j}^{E_{w2w}}$ is fed into the BiLSTM post encoder $E^{p2p}$ at time-step $i$.

When decoding, at the $k$-th step of the thread decoder $D^{t2t}$, post-level attention is computed $\gamma_{i}^k=Attention^\gamma(\textbf{h}_{k-1}^{D_{t2t}},\,P_i)\quad i\in[1,\,n]$ where $P_i$ is simply the representation $\textbf{h}_i^{E_{p2p}}$ for $i$-th post from the post-level encoder. The authors also argue that the phrases (short sequences of words in a post) in the documents are very important for abstractive summarization; thus phrase-level attention $\beta^{k}=(\beta_{0,\,0}^{k},\,…,\,\beta_{n,\,p}^{k})$ is computed as well, where $\beta_{i,\,j}^{k}=Attention^\beta(\textbf{h}_{k-1}^{D_{t2t}},\,\textbf{a}_{i,\,j})$ and $\textbf{a}_{i,\,j}=element-wise\,\,add(\textbf{W}_{i,\,j},\,\textbf{P}_i)\quad i\in[1,\,n],\,\,j\in[1,\,p]$ and $\beta_{i,\,j}^{k}$ is rescaled by the equation: $\hat{\beta}_{i,\,j}^{k}=\beta_{i,\,j}^{k}*\gamma_i^k$. A weighted representation of the word representations $\textbf{W}_{i,\,j}$ is given by: $\sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^p\hat{\beta}_{i,\,j}^{k}\textbf{W}_{i,\,j}$, which together with the last hidden state from the previous word-level decoder $\textbf{h}_{k-1,\,q}^{D_{w2w}}$ is fed into the thread-level decoder $D_{t2t}$ (shown in blue circle). The current state of the thread-level decoder $\textbf{h}_k^{D_{t2t}}$ is fed to a feed-forward network $g$ to obtain a distribution over $STOP=1$ token and $CONTINUE=0$ token, where $p_k^{STOP}=\sigma(g(\textbf{h}_k^{D_{t2t}}))$ and the decoder stops decoding if $p_k^{STOP}\gt 0.5$. Additionally, the extra two inputs $\sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^p\hat{\beta}_{i,\,j}^{k}\textbf{W}_{i,\,j}$ and $\textbf{h}_{k-1,\,q}^{D_{w2w}}$ together with the new state $\textbf{h}_k^{D_{t2t}}$ are fed to a two-layer feed-forward network $r$ with a dropout layer to compute the initial state $\textbf{s}_k$ for the unidirectional word decoder $D_{w2w}$.

At the $l$-th step of the word-level decoder inside the $k$-th step of the thread-level decoder, word-level attention $\alpha_{i,\,·}^{k,\,l}$ is computed and then rescaled as: $\hat{\alpha}_{i,\,j}^{k,\,l}=norm(\hat{\beta}_{i,\,j}^k\times \alpha_{i,\,j}^{k,\,l})$ where $norm(·)$ stands for softmax operation.

The construction of synthetic interleaved data is quite simple, which is basically randomly sample abstract-title pairs to consecutively construct threads and posts and corresponding summaries.

Highlights This work gives a specific way to construct interleaved data. However, I think the shining point lies in the proposed architecture of hierarchical attention, although it is quite complex, the experimental results show that the hierarchical attention can really disentangle the threads implicitly and performs better than models that disentangle threads explicitly.

-

Architecture:

See above

-

Paper:

AdaptSum: Towards Low-Resource Domain Adaptation for Abstractive Summarization [paper]

- Background and motivation:

Domain adaption for low-resource abstractive summarization is under-explored and this work hopes to set some baselines and references for future work.

-

Solution:

This work proposes three different tasks to investigate the effect of domain adaption in low-resource abstractive summarization on BART using second pre-training: a. Source Domain Pre-Training (SDPT), where the model is second pre-trained on a source domain (general, e.g., News); b. Domain-Adaptive Pre-Training (DAPT), where the BART is second pre-trained on an unlabeled target-domain-related dataset with the original BART re-construction objective; c. Task-Adaptive Pre-Training (TAPT), where the BART is second pre-trained on an unlabeled target-domain dataset with the summarization task.

For second pre-training, the model may face the problem of catastrophic forgetting and the authors tackle it using the RecAdam optimizer, which has the following training objective:

$$Loss=\lambda(t)·Loss_T+(1-\lambda(t))·Loss_S$$ $$where\,\,\lambda(t)=\frac{1}{1+exp(-k·(t-t_0))},\,\,Loss_S=\frac{1}{2}\gamma\sum_i(\theta_i-\theta_i^*)^2$$where $Loss_T$ is the target task objective function and $\theta_i$ is the parameter of the model and $\theta_i^*$ is the fixed original parameter of the pre-trained model.

Highlights I think the second pre-training and the proposal of three domain adaption tasks are very interesting, especially the tasks of SDPT and TAPT show their effectiveness in boosting the model’s performance in the low-resource setting (meanwhile, DAPT is not always very effective). And this work provides a new perspective about how we can boost the performance of abstractive summarization models through domain adaptation.

-

Architecture:

No specific overall architecture

Closing words

In this summary, we looked through six papers on the topic of performing abstractive summarization under a low-resource scenario, where different tasks and settings are discussed. We can see that these work can be roughly divided into two kinds: one is given a small number of labeled data, extra unlabeled data can be obtained and is used to generate synthetic data; two. only the given small number of labeled data can be used for training.

For the first setting, the key is to generate synthetic data / leverage extra data, and methods like back-translation ([here]), self-designed algorithm ([here]), domain adaption ([here]) are used. For the second setting, the key is to ONLY use the original data to enlarge the training data; thus, methods like paraphrasing ([here] and [here]) and compressing / pruning ([here] and [here]) are applied directly on the original data.

However, the above methods all generate new training data (from extra available data/original data) in a sequence-to-sequence manner within the same source (e.g., digits to digits), which means the augmented data is a transformation of the original data (e.g., $(1, 3,…,5,2)\in\mathbf{R}^n\longrightarrow (1,34,…,4,2)\in\mathbf{R}^n$) instead of a sequence-to-hidden-state manner (e.g.,$(1, 3,…,5,2)\in\mathbf{R}^n\longrightarrow (\vec{a_1},\vec{a_2},…,\vec{a_{n-1}},\vec{a_n})\in\mathbf{R}^{n\times m}\stackrel{aggregate}{\longrightarrow}\vec{A}\in\mathbf{R}^m$).

I think the method of directly generating its higher representation (hidden-state) may solve some challenges such as 1. the synthesized sequence may be grammatically wrong, 2. it may be irrational to generate synthetic documents with larger information from summaries using back-translation, etc.

However, this proposal may face the following problems: 1. the hidden-state may be hard to obtain and it varies for different models, 2. there may need a delicately designed architecture to map the digits to a higher representation (which may need to first prune the long, redundant documents first then aggregate their hidden representations to a concrete one, such as the initial state of the decoder).

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: